“Whoever beholds human beauty cannot be infected with evil; he feels in harmony with himself and the world.”

Goethe

“Goethe, as already indicated, I except; he belongs in a higher order of literatures than ‘national literatures’: that is why he stands towards his nation in the relationship neither of the living nor of the novel nor of the antiquainted. Only for a few was he alive and does he still live: for most he is nothing but a fanfare of vanity blown from time to time across the German frontier. Goethe, not only a good and great human being but a culture,”

Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human

This post is an interlude in my series on German philosophy following the introduction of Spinoza. It will more broadly discuss the cultural evolutions of the German nation during the late 18th Century and early 19th Century, through the lens of its greatest figure, Goethe, who so eminently represented the era of the greatest flourishing of the German genius. If you are not yet caught up, here are the posts in the series:

I. Drunk on God: Introduction to Spinoza

II. Reason’s Folly: Introduction to Jacobi and the Pantheismusstreit

IIIA: The All-Crushing: Introduction to Kant and Transcendental Idealism

IIIB: The Birth of German Idealism: The History of Post-Kantian Philosophy

Goethe, Genius, and Germany

The Heights of Culture

“Oh my friends! Why does the river of genius so seldom break forth, the flood tide so seldom rush in?”

Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther

“In Sturm und Drang, the intellectual and literary movement Goethe set in motion with Götz and Werther, the cult of genius was so widespread that the epoch has even been dubbed the Geniezeit, the age of Genius.”

Rudiger Safranski, Goethe: Life as a Work of Art

In a particular elementary school classroom in Germany during the 1780s, a teacher wished to distract his students so that he could attend to some work. As the class was on mathematics, he assigned them the task of calculating the sum of all the numbers between 1 and 100. This would both reinforce their comprehension of the basics of addition through mind-numbing repetition, and win the teacher some time. And yet within a minute of his announcing the task, one of the children piped up with the answer: 5050. The child had within the span of a minute derived the formula to reach the sum without any prior instruction. This boy was Carl Friedrich Gauss, whose immense contributions over the course of his lifetime would earn him the title of “The Prince of Mathematics.” Whereas every other boy in that class had begun their slow clumsy ascent through the application of basic concepts, he had immediately intuited the golden path. This is what genius consists in.

The term ‘Genius’ is applied to a wide variety of human specimens in honor of radically differing achievements, but is not for this reason without meaning. In the case of Gauss, his genius, like that of other great Mathematicians such as Euler or Euclid, is almost quantifiable in its evident demonstrable nature. In the case of one such as Themistocles, who for his political acumen and tactical instincts Thucydides called “a man who exhibited the most indubitable signs of genius,” the claim to the title is much more subtle. But whether their achievements are philosophical, logical, mathematical, political, military, or artistic, the unifying root which marks all such men under the univocal term ‘Genius’, is the immediateness with which they intuit the essential qualities of their respective subject. Goethe called this moment in which genius makes its lightning ascent the aperçu, a sudden insight which “prefigures the eternal in an original way. It needs no period of time to be convincing, but springs complete and perfect from the moment.” Where others may strive indefinitely, like Sisyphus, to attain the greatest heights of a particular discipline or domain of life, the genius soars on wings, guided by an immediate intuition of the essential nature of things. Genius is not something which can be attained, assembled, or simulated, but is rather the blessing of a particularly fortuitous nature present from birth.

The historical period whose philosophy this series has been discussing is that of the unparalleled fruition of the German genius. This is the era in which Kant blessed the world with his immortal insights, in which Mozart, Hadyn, and Beethoven completely transformed the horizons of Western Music, and in which great technical men such as Gauss were laying the foundations of the incredible scientific and technological advancements of the long 19th century. And yet upon this era, like a great golden seal, the name of one man has persisted, who more than any other defined the era and exhibited the vital possibilities lurking within it; Goethe. This post will discuss this golden age of German culture through the lens of its greatest titan, examining his long accomplished life and many influential works.

German Ascent and Decline

“Men possessed of great power of expansion, such as Goethe for example, traverse as much as four successive generations would hardly be able to equal; for that reason, however, they advance ahead too quickly, so that other men overtake them only in the next century, and perhaps do not completely overtake them, because the chain of culture, the smooth consistency of its evolution, is frequently weakened and interrupted.”

Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human

“Goethe is the last German I hold in reverence,”

Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

“This explains how the age when Kant philosophized, Goethe wrote poetry, and Mozart composed, could be followed by the present one, that of the political poets, the even more political philosophers, the hungry literati, carving out their existence by means of the lies and deceptions of literature, and the various ink-slingers who wantonly ruin the language.”

Schopenhauer, Parerga

When I first read Nietzsche as a teenager, the vehemence with which he condemned the Germany of his time left me somewhat confused. From my contemporary vantage point, Victorian Germany seemed like a magnificent nation, an industrial and scientific superpower which had achieved its largest territorial extent and was still capable of producing men like Wagner and Nietzsche himself. Reading the works of later German bourgeois such as Junger, Hesse, and Mann painted a picture in my young mind of a stable, cultivated society which seemed to me infinitely more elevated and enlightened than the environment which surrounded me. Yet the more I have familiarized myself with the era that preceded the Victorian, the more I began to despair alongside Nietzsche.

During the almost century separating Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos (1721) and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1824), Germany alone could boast of Hadyn, Mozart, Brahms, Schubert, Kant, Mendelssohn, Jacobi, Herder, Hamann, Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Schiller, Goethe, the Schlegel brothers, Humboldt, and so many others. This was a period of almost unparalleled cultural and philosophical activity. Germany, which had been somewhat of a cultural backwater compared to France and Italy for much of Western history, now had Austria as the center of European music and Weimar as a major hub of literary arts and philosophy. The 18th century is, for me, the cultural pinnacle of Western civilization proper. It contained so many promises which the 19th century failed to deliver on. Above the nausea of Romanticism for a moment emerged the phoenix-like return of the Classical, only for it to once more submerge beneath the jealous waves of half-thought religious sentiment, national barbarism, and decadent self-absorption.

In this period it was as if for a moment some distant breeze seemed to find its way across the centuries from antiquity, and cast its salt-laden air upon the forests of Europe. In Schopenhauer we find a throwback to the Classical philosopher, whose doctrine was not a mere product of abstract thought born of university corridors, but a way of life which expressed the deepest character of its progenitor. He stands apart from all of society, as if on some mountaintop, and raising the standard of truth launches his attack against all dogmas and doctrines, a hermit spitting venom at the world beneath him. Such a stubborn commitment to truth and instinctual contempt for all that was petty and base echoes the likes of Heraclitus and his own self-imposed exile. In Napoleon we once more witness the Classical great man, the imperator, a secular deity rising above the petty politics and Rousseauesque moralizing of his time and sweeping across the world by the sheer force of his spirit and character. Like Alexander he seized the world as a young man, and transformed himself into a glittering image of power and achievement which transcended the boundaries of nations and creeds, and inspired many Europeans with an inkling of a greater destiny than petty nationalisms.

And in Goethe we find an artist who hovered above all the decadent indulgences which would soon consume Western culture, guided by a supreme instinct for life in all its forms, a Renaissance man suckled by Homer and Shakespeare. He entered deeply into the bosom of the Romantic and the Gothic, and emerged unscathed to breathe fresh Classical air, fixing his gaze on the eternal rebirth of traditional cultural forms without ever wavering amid all the meaningless noise of the popular and fleeting. In each of these men there shimmer hints of a Europe which was only in its infancy, which would herald an entirely new kind of man. And yet they slip from the pages of history leaving humanity behind, and less than a century from the death of Goethe, in the very city in which he conducted the greatest heights of its culture, the German nation would degenerate into the likes of the Weimar republic.

The Age of Goethe

The Goethezeit: The Age of Goethe. That an era so overflowing with intellectual and artistic achievement, so fertile for the fruits of genius, could be summarized with the name of a single man is already the highest praise. Goethe is the flower of German culture, the greatest shoot it ever sprouted. If he was simply the author of Werther and Faust, he would be an unworthy portrait of his times. But Goethe was not only an artistic genius worthy of comparison with the likes of Shakespeare, but perhaps the most well-rounded man one can find in history, who lived life guided by an elevated instinct such that he never careened into any great excess, but made himself a master of every task which set itself before him. I must quote in its entirety the amazing section dedicated to Goethe from Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols.

Goethe—not a German event but a European one: a magnificent attempt to overcome the eighteenth century by a return to nature, by a coming-up to the naturalness of the Renaissance, a kind of self-overcoming on the part of that century.—He bore its strongest instincts in himself: sentimentality, nature-idolatry, the anti-historical, the idealistic, the ideal and revolutionary. He made use of history, natural science, antiquity, as well as Spinoza, and a practical activity above all; he surrounded himself with nothing but closed horizons; he did not divorce himself from life but immersed himself in it; he never lost heart and took as much as possible upon himself, above himself, into himself. What he wanted was totality; he fought against the disjunction of reason, sensuality, feeling, will (—preached in the most repulsively scholastic way by Kant, Goethe’s antipode), he disciplined himself into a whole, he created himself… In the midst of an age disposed to unreality, Goethe was a convince realist: he said yes to all that was related to him in this respect—he had no greater experience than that ens realissimum called Napoleon. Goethe conceived of a strong, highly educated man, adept in all things bodily, with a tight rein on himself and a reverence for himself, who can dare to grant himself the whole range and richness of naturalness, who is strong enough for this freedom; the man of tolerance, not out of weakness, but out of strength, because he knows how to turn to his advantage what would destroy the average type; the man to whom there is no longer anything forbidden except weakness, whether it be called vice or virtue… Such a liberated spirit stands in the midst of the universe with a joyful and trusting fatalism, with faith in the fact that only what is individual is reprehensible, that everything is redeemed and affirmed in the whole—he no longer denies… But such a faith is the highest of all possible faiths: I have baptized it with the name of Dionysus.

Goethe’s life: Overview

“It is a pleasure to behold a great man.”

Goethe, Götz von Berlichingen

There is perhaps no great man in history of whom we are better acquainted than Goethe. He was an artistic celebrity by his 20s and lived to the ripe age of 82 while remaining continually immersed in the world which surrounded him. He kept in contact with a wide circle of friends via letters throughout his entire life, documented the events of his travels and experiences in journals, and was actively involved in the civic life of his home city of Weimar. His long life enabled him to consciously concern himself with his legacy; he compiled an excellent autobiography, Poetry and Truth, which covers his ‘development’ period, the first 26 years of his life, and also published a recording of his travels through Italy as a young celebrity, The Italian Journey. And through his mentorship of the young poet Johann Peter Eckermann in his twilight years, a recording of his thoughts and conversations survives in Eckermann’s Conversations of Goethe, which Nietzsche aptly praised as “the greatest German book there is.” All of this is suffice to say that in Goethe we not only get to glean his genius from the fruits of his work, but can live alongside it in the recordings and recollections of the various periods of his life. This vast canvas is, in my opinion, the greatest cumulative insight into human genius available to a modern man.

Goethe’s life is one of constant productivity. His first great work was completed by the time he was 22, and his last major work, Faust, was completed in the years proceeding his death. Goethe is a particularly impressive figure because he never stopped in his quest for self-perfection. Where most artists settle into their apex form by a young age and only wane in their retirement, Goethe’s last work was his greatest, and in his conversations with Eckermann we behold a man who had truly fashioned himself into a work of art. Nietzsche throughout his various writing periods is frequently praising Goethe’s quest for totality. In no small part inspired by Spinoza, Goethe conceived of the world around him and within him as one great whole. He sought to invest himself in every part of it, raising himself towards his greatest possible form, his own creation. I will divide his life into three phases. The first phase is his youth as a sensitive young man who soared to popularity, and ignited the Romantic Sturm und Drang movement through his writings. The second is his maturation, where he began to turn away from Romanticism towards Classicism, threw himself into scientific and civic pursuits, and inaugurated the next great German literary movement in his productive friendship with Friedrich Schiller. The final phase of his life will be his time as an older man who never ceased working upon the canvas of his being. The figure which emerges from Eckermann’s Conversations undoubtedly greatly inspired Nietzsche’s conception of self-becoming.

I. A Sensitive Young Man

The Romantic Era

The 18th Century was a period of massive transformation which saw the political and religious foundations of the European order completely upended. Great Britain, France, and the Holy Roman Empire had emerged from the 17th Century with new political orders which had been forged in its brutal religious conflicts. Catholic Absolutism in France, Parliamentary Anglicanism in England, and a religiously and politically fractured Germany, divided between Protestant Prussia and Catholic Austria. The economic and political transformations each nation had endured during its time of crisis were already exhibiting significant consequences, as a new class of men took the stage.

A larger share of authority and wealth was being allocated to the rising bourgeois class who were increasingly the dominant force in the economy and civil administration. They had attained a sufficient amount of power and wealth to form a literate patron class beneath the aristocracy, to whom artists and intellectuals increasingly catered. It is during the early 18th century that the exuberant, explorative, and complex music of the Baroque shifts into the accessible, tuneful music of the Classical, such that Bach was looked back on for years as an obtuse relic. The Fugue is replaced by the Sonata to create art which is better suited to the expanding European audience and its tastes. I believe the great cultural achievements of the 18th century are partly due to a sort of balance achieved with the entrance of the bourgeoisie as a self-conscious class. A large talented segment of the population had now become literate and economically self-sufficient, but Western society had not yet economically and politically democratized enough for crude mass culture to become the victorious force.

The religious wars of the 16th Century and growing presence of the bourgeoise had occurred simultaneous to the dawn of the enlightenment. The larger literate share of the population, and the background of religious conflict, created a context suitable to the critique and consideration of philosophical questions outside the bounds of traditional orthodoxy. Descartes, Spinoza, Hobbes, Leibniz, and so many others lit a torch which the growing intellectual class would carry forward. A Rationalist, Neoclassical intellectual status quo blossomed and came to dominate the cultural corridors of Europe. But the inherent contradictions between this new intellectual radicalism and the traditional organs of dogma and power would become increasingly explosive, till they finally overflowed at the end of the century with the bloodshed and revolt of the French Revolution.

The first phase of Goethe’s life corresponds to the youth of all the important radicals of the late 18th and early 19th century. Under the auspices of these great transformations, a massive generation of literate, educated, young bourgeois and aristocratic men were coming of age. The enlightenment had revealed the boundless possibilities for European intellectual, religious, and political life, and these new men balked at the cold, conservative political and cultural authorities which wanted to arbitrarily stop the flow of critique and liberation before it could undermine the religious and political dogmas of the time. These radicals would experience their era as one of backwardness and suppression, which they increasingly revolted against. This is the era of Romanticism. This is the environment into which Napoleon was born.

Goethe’s Childhood

Goethe was born in Frankfurt in 1749, one year before the death of Bach. He was the grandson of the mayor, and enjoyed a prosperous upbringing. Reading Goethe’s account of his youth in Poetry and Truth gives a quite idyllic image of his childhood. This is modernity at the final stage of its infancy; Holy Roman Emperors gather for their coronation beside children who will live to see Napoleon dissolve the Reich, eminent cities such as Frankfurt still boast hardly 50 thousand members, and beyond the limits of urban hubs stretch the open expanses of nature. In his later writings, such as Faust and Wilhelm Meister, visions of this idyllic 18th century Germany with its quaint towns and rolling fields often appear.

This idyllic period of youth, which all excepting the particularly unfortunate have experienced in some capacity, came to an end for Goethe as it does for everyone; amid the tumult of awakening maturity. The boy had gained a reputation for his poetic skills, and a group of young people approached him with assignments of silly poems they wanted written. Goethe abided, in no small part due to the influence of a waitress named Gretchen who formed part of the company. Goethe became obsessed with her, his first love, and vividly describes attending the coronation ceremony for Joseph II at age fifteen while holding hands with her. This momentary joy transformed into profound embarrassment, as it was revealed that the youths had engaged Goethe in an attempt to ensnare his powerful Grandfather. Gretchen was forced to leave town, but not before confessing she had only seen the boy as a little brother figure, and used her charms to manipulate him. You can imagine the humiliation the teenage boy experienced.

Like all great men, Goethe never had in mind any static domestic life. In the wake of his painful teenaged experiences, the young man set out at 16 for an education. He, who had long been enamored by Homer in particular, desired to go to Gottingen to study the ancients under the tutelage of some of the most celebrated Classicists of the era. His father, however, wanted the boy to follow in his lawyerly footsteps, and sent him off to Leipzig instead. Goethe found his legal education incredibly boring, and returned home not long later a despairing dropout suffering from illness, and only returned to and completed his studies a year later in the city of Strasbourg.

Herder, Götz, and Prometheus

“[Goethe] has what one calls genius and an extraordinarily lively imagination. He is intensely emotional. He has a noble way of thinking. He is a man of character. He loves children and can become very involved with them. He is bizarre, and there are various things about his behavior and appearance that could make him unpleasant. But nevertheless, he is in the good books of children, women, and many others.—He does whatever occurs to him without worrying whether it pleases others, is fashionable, or permitted by good breeding. He hates all constraints.—He holds the female sex in high regard.—In principiis he is not yet settled and is still searching for a certain system…. He is not what one would call orthodox, however not from pride or caprice or to make a show. (…) He has made belle-lettres and the arts his principal study—or rather, all branches of knowledge except those by which one earns one’s bread…. He is, in a word, a very remarkable person.”

Description of Goethe in his early 20s from Johann Kestner

“In my thoughts it pleased me to make my natural gift the foundation of my entire existence. This idea was transformed into an image: the old mythological figure of Prometheus occurred to me… The story of Prometheus came alive within me. I altered the old robe of the Titans to fit my size.”

Goethe

“Herder is none of the things he induced others to suppose he was (and which he himself wished to suppose he was): no great poet and inventor, no new fruitful soil full of fresh primeval energy as yet unemployed. He did possess, however, and in the highest degree, the ability to scent the wind; he perceived and plucked the firstlings of the season earlier than anyone else, so that others could believe it was he who made them grow,”

Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human

It was in Strasbourg that Goethe would finally come into his own, in no large part due to the influence of one of his earliest mentors; Herder.

“The Enlightenment had developed its image of man from the starting point of human reason, as if it were the strongest, most decisive faculty. As a result, society and morality were intellectualized and viewed with an eye to their utility. Like a German Rousseau, Herder rebelled against this line of thought. He aimed to loosen sclerotic systems, dismantle their conceptual structures, and take hold of life, understood as the unity of intellect and nature, reason and feeling, rational norm and creative freedom.”

Rudiger Safranski, Goethe: Life as a Work of Art

Johann Gottfried Herder, five years Goethe’s senior, was already a celebrity by the time of their acquaintance. A great critic of the Aufklarung and a romantic defender of subjective feeling against the objective tyranny of reason, he introduced Goethe to a host of new ideas as well as Shakespeare, who Goethe worshiped for the rest of his life.

“[Shakespeare]’s plays all revolve around that hidden point (which no philosopher has ever seen or determined) where the uniqueness of our self, our supposed free will, collides with the necessary course of the world.”

Goethe, On Shakespeare’s Day (1771)

Goethe would maintain that many of the ideas Herder articulated had already been forming independently within him, but it is undeniable that Herder’s philosophy had a great influence on the early Goethe and the Sturm und Drang Romantics who followed him. A Romantic individualism, it conceived of the artist as a dynamic self-determining member of a larger folk who must reconcile his objective reason with his subjective sentiments.

Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) was the movement of young German romantics which emerged in the ~1770s in revolt against the Neoclassical enlightenment sensibilities in literature, primarily inspired by the works of Goethe and the thought of Herder. The first major work which Goethe produced and which catapulted him to minor celebrity was the play Götz von Berlichingen. Based on the historical personage of a knight from the Reformation, Goethe created a play setting Götz as the rebellious representative of a dying era of wild, rough, free men. The influence of Shakespeare, with whom Goethe was at the time completely enamored, is evident in the story of a lone tragic figure, larger than life, standing against seemingly the entire world. The attitude towards Götz which Goethe and his fellow romantics had is comparable of that of 20th century Americans to the cowboy. The image of the forever warring mercenary, zweihander in hand, stumbling through history always defiant (the actual Götz estimated he had fought 19 blood feuds) shone brightly to them as a model completely inimical to the enlightenment ideal of the sensible, rational, social man who had exiled his heart in favor of his head. Perhaps the most famous line from the play is taken from Götz’ life, where when asked to surrender to the Swabian alliance he reportedly replied Er kann mich am Arsch lecken! (He can lick my ass!).

Götz impressed many of Goethe’s friends as he shared the manuscript, but prior to its publication he could hardly justify quitting his legal career, and so he continued his practice, eventually moving to the village of Wetzlar for his legal work. It would be here that he would receive the painful inspiration for arguably the greatest Romantic novel ever produced, and one of the first truly pan-European cultural events. This chain of events began innocently enough with his entry into the intellectual society of Wetzlar where, at a small dance organized at a hunting lodge, he met Charlotte Buff. The young girl with curly blonde hair and sky blue eyes instantly captured his heart, though he soon discovered to his misery that she was already engaged. Goethe would nevertheless pursue her friendship, with the support of her fiancé Johann Kestner who likewise became his friend, till he found himself sunk in an infatuation which could lead nowhere. It seems even geniuses can find themselves in the friendzone! Realizing the situation could only perpetuate suffering for all parties, he departed in secret in 1772, leaving a letter for each of Johann and Charlotte.

With the publication of Götz in 1773, Goethe quickly became one of the most famous names in German literature, with the play widely beloved by the German public, even as Frederick the Great declared it a ‘vile imitation of bad English plays’ (Shakespeare). Since a young age Goethe had been convinced of his own genius, and the most frequent first impression which we encounter in the letters and records of his contemporaries is that of a bold and confident young man. But with his talents now nationally recognized at such a young age, the artist felt a surging sense of power and ambition which he delighted in. An offspring of this period was the poem Prometheus whose role in the Pantheism Controversy I discussed in my post on Jacobi. Prometheus is Goethe reveling in his own talent, taking on the role of a God-defying Titan rejoicing in his own creative powers. It would not be published till Jacobi released it in 1785 without Goethe’s permission. Prometheus came to not only represent the Romantic ideal of the artist as a creative self-determined individual, but for Lessing and other free thinkers, a raging polemic against dogmatic adherence to traditional faith.

Werther : Romanticism and Atomization

“The human race is a monotonous affair. Most people spend the greatest part of their time working in order to live, and what little freedom remains so fills them with fear that they seek out any and every means to be rid of it.”

Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther

The celebrity Goethe had won with Götz was insignificant compared to what came next. In the span of only three months in 1774, Goethe spun out a novel based on his experience in Wezlar as the third wheel to an engaged couple, the suicide of an acquaintance, and an even more recent love affair with an eighteen year old engaged to a middle aged merchant. The novel is written in an epistolary form as letters to a friend from a young artist, Werther, who has sought refuge in the fictional village of Wahlheim. Like Goethe, he falls in love with a woman already engaged, also named Charlotte, and her fiancé, Albert. Eventually his dashed hopes become too much for him; the young man flees back to the city. He tries to socialize and distract himself only to have a ‘my feet hurt’ moment at an aristocratic party he accidently enters. He is looked down upon as a young bourgeois, and finds himself humiliated and ejected from the gathering. Werther returns to the village, now in a state of constant agony as Charlotte and Albert have married, till finally he borrows Albert’s pistols under the pretense of going hunting, and commits suicide.

The Sorrows of Young Werther is the Romantic novel par excellence. Werther is fiercely individual and passionately involved in his own feelings, such that reason is unable to save him from his melancholy. Ostensibly it is a book about unfulfillable love, and it will indeed strike a chord with anyone who has been lovesick. But more than that, I believe Werther is about a particular state of mind. Nowadays it would be filed under the label of depression and lumped in with every other miserable affliction, but this is a very particular mental island, familiar to the youth of any man of intellect. If we look back to Götz as the kind of man Goethe and other romantics nostalgically envied, I think we can better understood what it was that Goethe was tapping into with Werther.

Götz is the man of power, a free-spirit for whom there is always a further battle. Even though his fate is tragic, his spirit is never defeated, his final words are a cry of freedom. Werther in contrast is the story of the man who has been reduced by his environment to a mental slave, who feels as if every horizon is empty and the whole of modernity stretches out in front of him without any great task which speaks to him. The peaceful environment of Werther, the idyllic village and the aristocratic town, could not form a sharper contrast to the chaotic age of knights, bandits, feuds, and murders which Götz harkens back to. In the absence of great tasks and opportunities, the young man retreats inward, into the subjective world of passion, literature, and decadence. I think the lovesickness is secondary; the reason Werther will be immediately sympathetic to the sensitive young man is because he is a fellow child of modernity, who faced with the crushing mundanity of his existence, falls beneath the seductive spell of melodrama and passion, of Romanticism. Werther is burdened by his Romantic ideals in a way reminiscent of Don Quixote’s retreat into chivalric literature, but deprived of the latter’s madness he only finds reality painfully disappointing. No matter where he flees it always fails to meet his expectations, he feels as if he has no place in it. And so his genius withers beneath the free range of his passions, and the young man is lost.

Supposed radicals love to talk about the “atomization” which is a feature of modern life, and there are a million screeds written by half-wit wannabe internet celebrities on the topic. Atomization is frequently framed as a consequence of liberal individualism and capitalism, as if millions of men in the West are suffering from an excess of freedom and self-sufficiency. But Werther reveals what atomization really is: a turning inward into private life and mental theater because there is no exterior world to engage with, no opportunities for power and activity available. The reason a man like Napoleon read Werther seven times, carried it with him everywhere on campaigns, and took time to personally discuss it with Goethe, was not because he was lovesick. When he was 16 the future emperor wrote the essay On Suicide in which he bemoans:

“Always alone and in the midst of men, I come back to my rooms to dream with myself, and to surrender myself to all the vivacity of my melancholy. In which direction are my thoughts turned today? Toward death.”

Compare this to Werther’s answer to his inability to find an exterior outlet for his talent and intellect as he is stuck as a guest and spectator to others lives:

“I turn back into myself, and find a world.”

Werther

Is Napoleon’s youthful melancholy not the same sickness which grips Werther, of which his fixation on Charlotte is only an exterior symptom? I’m sure many of you, my brethren, have felt those words of Napoleon with all your heart. This is what Werther captures, and what made it so madly popular. Women loved the romantic story oozing with sensitivity and emotion, but millions of young European men saw in it a reflection of their own ennui. Goethe’s ability to artistically intuit the nauseating transformations of modernity would only increase in his lifetime, with Faust being The modern epic.

Werther really ought to be read in your youth. It is the transfiguration of the youthful Romantic yearnings and sufferings of an artistic genius, a sensitive young man, into a text which is instantly accessible to anyone who has lived through that sort of period, that melancholic youth which one cannot fault oneself for, but nevertheless remembers with a certain embarrassment. With age and maturity that emotional way of life acquires a different flavor, becomes too saccharine, and we must, alongside Goethe himself, look back on it as something which had its proper place. He often described the writing of Werther as a purgative process for himself, and while so many of his era and the 19th century succumbed to that decadent retreat into the subjective which the book captures, Goethe himself continually sought out the exterior world and new trials, and strove for an objective, Classical, aesthetic sensibility.

In no time following its release Werther swept across Europe like a wildfire. Young men began dressing in the iconic blue and yellow outfit of the protagonist, and there were even reports of several imitation suicides which prompted a reaction reminiscent of modern scares over certain music genres or artistic mediums, Leipzig going so far as to ban the book and outfit in 1775. There was hardly a man who was born in the latter half of the 18th century who was not impacted by Werther. At the time however there weren’t real copyright laws, so although it won Goethe incredible fame, it hardly made him a prince. But fame was enough: in 1775 the young Duke of Weimar would invite Goethe to join his court as an advisor.

Conclusions

Goethe had summoned the sentiments of his generation, and won international celebrity through his ability to crystallize them in Werther. The novel captured the general reaction of young men faced with what they perceived as a stagnant, corrupt order, and constricting modern life: a turning inward, an embrace of all that was subjective and full of color, the transference of their energy which had no exterior outlet to the free play of imagination and self-absorbed melodrama. Spinoza was already seeping his way into the metaphysical vision of the generation, and within decades the German philosophical consensus would be decidedly Spinozist. For now these young men would content themselves with their books, plays, and heretical manuscripts, but the time was coming when they would blow the entire structure asunder. At the same time that Goethe was beginning to write Götz, the French monarchy annexes the island of Corsica, where that very year a child is born to the house of Bonaparte…

II. Maturation and Expansion

“This desire to raise up as high as possible the pyramid of my existence—whose basis and foundation were given to me—outweighs everything else and can hardly be forgotten even for a moment. I dare not tarry. I am already at an advanced age, and perhaps fate will break me in the middle of life and the Tower of Babel will remain an incomplete stump. At least they should be able to say it was a daring attempt.”

Goethe (age 31), Letter to Lavater 1780

The Revolutionary Era

The philosophical environment of the 1770s to 1780s is something this series has already covered in my posts on Jacobi and the beginnings of German Idealism, but parallel with the Philosophical revolution of Kantianism and Spinozism was a rising political and social radicalism which culminated in the French Revolution. While the Revolution erupted in France, the greatest European nation of the time, the intellectual vision propelling it also existed in Germany. There was a large initial support for the Revolution among German intellectuals, with Nietzsche claiming that only Goethe of his contemporaries experienced the Revolution as one ought to; with nausea.

An event which beautifully demonstrates the rapid change of the period is the transference of Voltaire’s remains to the Pantheon. The Revolution was more the offspring of Rousseau than Voltaire, yet he remained a powerful representative of the yearning call for change which had emerged in the 18th century. When he had died in Paris in 1778, he was denied a proper burial due to his criticism of the Catholic Church, and was only buried in secret with the aid of a relation of his. Jump forward only thirteen years, and in 1791 the National Directory had him interned in the French Pantheon, in a procession which reportedly drew a million Parisians. The exiled critic, who even remained an exile in death, was now a secular deity enshrined in the nation’s most sacred hallow.

The young men whose angst Goethe had precipitated with Werther were now becoming an active and fiercely idealistic part of society. This idealism would be sharply demoralized as the grandiose aims of the Revolution quickly transformed into vulgar bloodshed, as is always the case with such things, but their calls for further change would continue to resound. Goethe however had already outgrown his era, and beheld a new vision which surpassed the childish Romanticism of his contemporaries. While the rest of the 18th century fell in love with the democratic, nationalist, and Romantic image of the Revolution, Goethe would fall in love with the imperial, cosmopolitan, and Classical image of Napoleon. It would be in Weimar that he overcame his Romantic youth, and blossomed into the man Nietzsche and Schopenhauer worshipped.

Goethe the Practical Man

The Duke of Weimar, Karl August, was a young man only a couple years Goethe’s senior. The Duke’s father had pre-deceased him by the time he was one years old, and his mother had consequently ruled the Duchy as regent from 1758 until her son assumed control in 1775. His mother was a major patron of the arts, and under her regency Weimar had become one of the great cultural centers of Europe. One of the first actions Karl took upon his ascension was to invite Goethe, whom he had previously met in Frankfurt, to court in the hopes of continuing Weimar’s role as a cultural center. This wise decision would win him a lifelong friend, transform Weimar into the home of German literary culture, and add a capable administrator and advisor to his inner circle.

Goethe’s youth had been one fraught with love affairs and a Romantic sensibility which frequently submerged him into long states of melancholy. His move to Weimar initiated a new era of his life which saw the young artist transformed into a man of manifold talents. During his time in Weimar he would assume a major role in government and embrace a new practical dimension to life. Goethe directed himself into his tasks with great passion. One of his favorite roles was the management of the Duchy’s mines, the image of overcoming the tenebrous deeps of the earth through technical ingenuity greatly enchanting him. He took the opportunity to learn about geology and the earth, which became only a small part of his increasingly expansive scientific interests. It is no wonder that Nietzsche saw in him the brief return of the Renaissance. Like Cellini, whose biography Goethe translated into German, Goethe was driven by a lust for life in all its dimensions. He escaped the kind of Romantic self-image artists like Beethoven or Berlioz inhabited, wherein the artist is entirely devoted to his craft and must scoff at the rest of the world, such that he considered his accomplishments in the science of colors to be as much as source of pride as his great literary works.

“I came to Weimar quite ignorant of all nature study, and only the need to give the duke practical advice in his various undertakings—construction projects, parks—drove me to study nature. Ilmenau cost me much time, trouble, and money, but in exchange I also learned something and acquired a conception of nature that I would not trade at any price.”

Goethe, Letter to Jacobi

Herder, who had followed Goethe to Weimar and whose ego was stung by his former inferior’s new position, bitterly described Goethe’s status in Weimar in 1782 with the following words:

“So now he is really a privy councilor, finance director, chairman of the military commission, supervisor of construction down to the level of road buildings, and in addition director of recreations, court poet, the author of pretty festivities, court operas, ballets, masquerades, inscriptions, works of art, etc., director of the academy of graphic art where in the winter he delivered lectures on osteology; is himself everywhere the first actor, dancer—in short, the factotum of Weimar and, god willing, soon the major domo of the entire Ernestine branch of the House of Wettin, among whom he circulates in order to be idolized. He has been made a baron, and on his birthday (…) his ennoblement will be announced.”

It was during this period in the 1770s and 80s that Goethe’s philosophical interests became more pronounced. On the urging of his friend Jacobi, he began studying Spinoza in seriousness, who became one of his great intellectual influences. He would keep up with the philosophical revolutions of the post-Kantian age, speaking with all the major German Idealists: Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, and Schopenhauer. It would be his intercession which would secure the first two their posts at the university of Jena, which was in the Duchy and the center of post-Kantian philosophy until Hegel and Schelling’s eventual migrations to Berlin.

Goethe’s own philosophical views fall within the purview of my series broader story. Like many other Germans, the influence of Spinoza had reoriented Goethe’s metaphysical views with those of the ancients whom he idealized. Describing himself as “not anti-Christian, nor un-Christian, but most decidedly non-Christian,” Goethe was infamously known as a freethinker who affirmed a faith in a God which transcended Christian dogma. Inspired by Spinoza, he cultivated his own Pantheist philosophy centered around the ideals of activity, totality, and eternity. Where nature for the Romantics had been a saccharine symbol of purity, Goethe’s maturation in Weimar saw him form a conception of nature as an object of scientific understanding, and source of insight into the essence of the world.

“In Goethe a kind of almost joyous and trusting fatalism that does not revolt, that does not flag, that seeks to form a totality out of himself, in the faith that only in the totality everything redeems itself and appears good and justified.”

Nietzsche, Will to Power

The Italian Journey : The return to Classicism

“Romanticism is sickness, Classicism is health.”

Goethe

“My tendencies were opposed to those of my time, which were wholly subjective; while, in my objective efforts, I stood alone to my own disadvantage.”

Goethe, Conversations of Goethe

Although Goethe had overcome the civic tasks which had been assigned to him, adapting himself to their rigid requirements and technical subjects, once more that vital instinct within him saved him from excess. He recognized that he was growing distant from his artistic nature, was repulsed by the self-absorbed and vulgar character of his Romantic youth, and longed to renew himself as an artist in the bosom of the ancient world which had so long enchanted him. For that reason, in 1786 he left Weimar in secret on a trip to Italy, to rediscover the aesthetic sensibility of the ancients, in imitation of similar southern migrations by Winckelmann and even his own father. This journey would be a transformative experience which Goethe documented and published as his famous Italian Journey, and which inaugurated a new period in his art, and by extension German culture as a whole.

I would now like to take a moment to quote at length once more from Nietzsche, who idolized Goethe especially for his later period, and whose words are incredibly relevant to this shift from Romanticism to Classicism within Goethe.

“And does the mature artistic insight that Goethe achieved in the second half of his life not at bottom say exactly the same thing?— that insight with which he gained such a start of a whole series of generations that one can assert that on the whole Goethe has not yet produced any effect at all and that his time is still to come? It is precisely because his nature held him for a long time on the path of the poetical revolution, precisely because he savored most thoroughly all that had been discovered in the way of new inventions, views and expedients through that breach with tradition and as it were dug out from beneath the ruins of art, that his later transformation and conversion carries so much weight: it signifies that he felt the profoundest desire to regain the traditional ways of art and to bestow upon the ruins and colonnades of the temple that still remained their ancient wholeness and perfection at any rate with the eye of imagination if strength of arm should prove too weak to construct where such tremendous forces were needed even to destroy. Thus he lived in art as recollection of true art: his writing had become an aid to recollection, to an understanding of ancient, long since vanished artistic epochs. His demands were, to be sure, having regard to the powers possessed by the modern age unfulfillable; the pain he felt at that fact was, however, amply counterbalanced by the joy of knowing that they once had been fulfilled and that we too can still participate in this fulfillment. Not individuals, but more or less idealized masks; no actuality, but an allegorical universalization; contemporary characters, local color evaporated almost to invisibility and rendered mythical; present-day sensibility and the problems of present-day society compressed to the simplest forms, divested of their stimulating, enthralling, pathological qualities and rendered ineffectual in every sense but the artistic; no novel material or characters, but the ancient and long-familiar continually reanimated and transformed; this is art as Goethe later understood it, as the Greeks and, yes, the French practiced it.”

Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human

Romanticism was thoroughly subjective; it emphasized individuality, sensitivity, and vivid feeling. Classicism was thoroughly objective; it emphasized the archetypal, rational, and self-controlled. Goethe increasingly moved from the former end of the spectrum towards the latter, and his journey through Italy provided him distance from his prior work, which he had begun to look back on with some dissatisfaction.

“Ask, now, whoever you wish, you’ll not reach me,

Lovely Ladies, and you, fine Men of the World!

‘Did Werther really live?’ ‘Was it really so?’

‘Which town can truly claim Lotte as resident?’

Ah, how often I’ve cursed those foolish pages,

That showed my youthful sufferings to everyone!”

Goethe, Roman Elegy II

He traveled about Italy recording his activity in the journal which would form the substance of the Italian Journey, and received inspiration for his erotic poems, the Roman Elegies. But it is with his return from Rome that Goethe’s next period of artistic activity began, one which would transform German culture once more.

Weimar Classicism: Schiller and Wilhelm Meister

"'But,' said Wilhelm, 'shouldn't natural talent be all that an actor...needs to enable him to reach the high goal he has set himself?'

'That should certainly be, and continue to be, the alpha and omega, beginning and end; but in between he will be deficient if he does not somehow cultivate what he has, and what he is to be, and that quite early on. It could be that those considered geniuses are worse off than those with ordinary abilities, for a genius can more easily than ordinary men be distorted and go astray.’”

Goethe, Wilhelm Meister

“Where we were looking for pleasure, happiness and joy, we often find instruction, insight and knowledge, a lasting and real benefit in place of a fleeting one. This idea runs like a bass-note through Goethe's Wilhelm Meister; for this is an intellectual novel and is of a higher order than the rest.”

Schopenhauer

Upon his return to Weimar, Goethe turned his focus to the cultural cultivation of the Duchy, rather than the administrative tasks that could be performed by others. He fell in love with a young orphan, Christiane Vulpius, who he kept as a scandalous mistress for decades, till he eventually married her during Napoleon’s invasion. It was in this period of political revolution that a philosophical revolutionary emerged: Fichte. Goethe prided himself on securing for the duchy the great talent of the first of the major German Idealists, who replaced Reinhold as the chair of Kantian philosophy at the nearby university of Jena. Fichte’s philosophy, greatly inspired by Spinoza, appealed to Goethe with its dynamism and emphasis on the subject’s activity.

“Recently he described my system to me so clearly and concisely, that I couldn’t have done it more clearly myself.”

Fichte, Letter to his wife in reference to Goethe

Fichte and the post-Kantian era ignited a renewed interest for philosophy in Goethe which led him to strike up a friendship with fellow artist Friedrich Schiller. Schiller had risen to fame through his play The Robbers, and was a fellow product of the Sturm und Drang period. Goethe was initially put off by Schiller, who he found too much on the romantic/subjective end of the spectrum for his tastes. With time however, he began to recognize the immense talent in the younger artist. Schiller’s philosophical passion (his Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man was an immense Kantian contribution to aesthetics) provided the pretense for the two to become closer after 4 years of acquaintance. Their productive relationship would last seven years until Schiller’s death, and see the two collaborate on a wide body of literary work and art criticism which cemented the pair as the fathers of modern German culture. They sought to fuse the feeling and passion of Sturm und Drang with the austere elegance of Neoclassicism: the result was Weimar Classicism.

It was during this period that Goethe began work on his second novel, Wilhelm Meister Apprenticeship. The text is a bildungsroman, the story of a young man’s education and coming of age. The novel could not have better demonstrated his personal evolution since the writing of Werther. Considered by Schopenhauer one of the four greatest novels ever written, and the model upon which Thomas Mann created his own bildungsroman masterpiece The Magic Mountain, Wilhelm Meister is a literary masterwork documenting a young artist's journey of self-realization. It is an explicit commentary on the conditions of genius and its cultivation.

Wilhelm Meister is a young bourgeois who passes time by organizing puppet shows among the children of his village, and who longs to become part of a theater company in order to realize his dreams of being an artist and of elevating German culture. He leaves home on a business trip, as his father wants him to inherit the family trade and become a merchant, and on his travels meets a theater company which he ends up joining. Much of the book records his journey with the company and their attempts to adapt and perform Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The book is full of philosophical discussions concerning the nature of genius, the artist, and aesthetic criticism of Shakespeare and German literary culture. Wilhelm increasingly realizes the folly of his dreams of elevating German culture, as members of the troupe ignore his high-minded ideals in favor of philandering and alcoholism, and they end up catering to the low tastes of the public. It is at this point that Wilhelm encounters a secretive circle of nobles, who encourage his aesthetic and personal growth. Over the course of the final act of the novel they discretely submit him to a series of tests, before initiating him into the ‘Society of the Tower’: a secret brotherhood dedicated to the elevation of man.

It is revealed that the society has been guiding Wilhelm on his journey, his apprenticeship, for a long time. The Society’s goal is to aid talented natures in cultivating a balanced, harmonious spirit. They believe that genius is a precarious gift, and that every young man of intellect must struggle to maintain a balance between the ideal and the real, the exterior and the interior, the subjective and the objective. The society members believe in treating human beings as works of art, multifaceted beings who must fashion themselves into harmonious totalities. In other words, they must avoid becoming lopsided self-destructive specimens like Werther, and not waste their genius. The novel takes a strange circuitous route near the end, reflecting the difficulty Goethe had in coming up with a suitable ending, until the protagonist decides to go on a journey with his newly discovered son, having overcome his Romantic desire to become an actor, instead aspiring to learn about the human form and become a surgeon. There is a clear connection between this narrative arc and Goethe’s own transformation from the melancholic author of Werther to a more fully developed man through his engagement with practical affairs. When I first read Wilhelm Meister as a teenager, the idea of the Society of the Tower affected me deeply. The ideal of men of spirit banding together and forming a parallel society with the pure goal of cultivating young talents, of remedying their excesses in the pursuit of totality, this resonated with me as the end goal of civilization itself. “Life as a Work of Art”; is this not the idea that animated Nietzsche, Mishima, and all other free spirits?

Schiller and Goethe collaborated on Wilhelm Meister, though their differences frequently emerged in its production. Schiller was the prophet of freedom, of liberation and transformation through effort, and objected to the hero’s journey being directed by the machinations of some nobles. He had been an early exponent of the French revolution, and had reacted with horror to Napoleon; the inverse of Goethe’s response. Goethe’s aristocratic sensibility, his vision of a dancing effortless talent endowed by nature, irritated Schiller who had always somewhat envied Goethe’s seeming ease of success. Goethe had no problem with the intervention of the society of the tower because to him they were merely external expedients of Wilhelm’s own natural genius.

“[Schiller] preached the gospel of freedom; I wanted to make sure the rights of nature didn’t come up short.”

Goethe

In 1796, Goethe also began to cultivate a relationship with the young Schelling, who was already becoming famous as the next great Kantian after Fichte, and who was a close friend and future opponent of his roommate Hegel. Schelling’s philosophy constantly evolved throughout his life, but its main focal point was an emphasis on nature as an autonomous creative force, rather than a mere object fashioned by the subject’s laws. His belief in mind as unconscious nature, and nature as unconscious mind, deeply appealed to Goethe’s philosophical sensibilities, who invited him to Jena 1798 as a replacement for Fichte, who had been removed due to Jacobi’s accusations of atheism.

Conclusions

You know that, on the whole, I care little what is written about me; but yet it comes to my ears, and I know well enough that, hard as I toiled all my life, all my labors are as nothing in the eyes of certain people, just because I have disdained to mingle in political parties. To please such people I must have become a member of a Jacobin club, and preached bloodshed and murder.

Goethe, days before his death

The 1780s and 90s were some of the most transformative years in Western history. The French Revolution brought to bear the democratic sentiments which had been festering for decades, and initiated a process which would eventually end the cosmopolitan network of aristocracies which had constituted the bedrock of European political and cultural life for a thousand years, and give rise to the exhausted popular nation-states which litter Europe’s carcass today. At the same time as this transformation, Goethe hovers above as a reminder of what Europe was truly capable of, what it could have chosen instead. Never falling prey to the political idealism of people like Schiller, he remained a steadfast conservative ally of aristocracy and nature who believed in a culture which rose above the childish tastes of the people. He was at heart a steadfast initiate of The Tower Society, whose self-imposed task was the cultivation of his own and other geniuses. But Goethe could rejoice, for he would soon meet another titan who intonated at greater European possibilities. In the violent streets of revolutionary Paris, a young 26 year old officer, who had written of his inward retreat into melancholy and identified so deeply with Werther a decade earlier, would calmly order his men to fire that ‘whif of grapeshot’, as Carlyle dubbed it, at the waves of human beings approaching him, ending the French Revolution by coating the streets with blood.

III. Life as a Work of Art

“I described Bonaparte as a representative of the popular external life and aims of the nineteenth century. Its other half, its poet, is Goethe, a man quite domesticated in the century, breathing its air, enjoying its fruits, impossible at any earlier time, and taking away, by his colossal parts, the reproach of weakness which but for him would lie on the intellectual works of the period. He appears at a time when a general culture has spread itself and has smoothed down all sharp individual traits; when, in the absence of heroic characters, a social comfort and cooperation have come in. There is no poet, but scores of poetic writers; no Columbus, but hundreds of post-captains, with transit-telescope, barometer and concentrated soup and pemmican; no Demosthenes, no Chatham, but any number of clever parliamentary and forensic debaters; no prophet or saint, but colleges of divinity; no learned man, but learned societies, a cheap press, reading-rooms and book-clubs without number. There was never such a miscellany of facts. The world extends itself like American trade.”

Emerson, Representative Men

Out of nowhere amid the democratic revolt in the Western spirit there emerged a man on horseback. Napoleon dragged his delicate fingers across the manifold puppet strings that hung above the era, and grabbed hold of them through a monstrous egotism. For a time he eclipsed what had seemed like the inevitable course of history, the nationalization and democratization of Europe, and forced it into a great battle of imperial proportions, summoning a whole cast of military heroes to the fore of history.

The final third of Goethe’s life saw him slip into the role of the elderly father of German culture, watching its decline with a concerned eye. In the years between 1800 and his death in 1832, he would complete his great masterpiece Faust upon which he had been working his entire life, publish new collections and editions of his life’s work, and converse with some of the great talents and intellects of his time. I would like to conclude this examination of the man by looking at some of his relationships from this period, and the crowning achievement of his artistic career, Faust.

The clear disjunction between the outlooks of Goethe and his Romantic contemporaries by the 1800s is perhaps nowhere better exhibited than during the Teplitz incident of 1812. Goethe and Beethoven, who had admired each other’s work, finally met at the spa of Teplitz. While the two were out talking, the Empress of Austria approached alongside a company of retainers and fellow nobles, to which Goethe responded by taking off his hat, bowing, and greeting them. Beethoven, a Romantic disciple of the Revolution, held his hat on his head, and made a point of rudely pushing through the crowd. Goethe would be permanently put off by Beethoven for this display.

[Beethoven’s] talent amazed me. However, unfortunately, he is an utterly untamed personality, who is not altogether in the wrong if he finds the world detestable, but he thereby does not make it more enjoyable either for himself or others. He is very much to be excused, on the other hand, and very much to be pitied, as his hearing is leaving him, which, perhaps, injures the musical part of his nature less than his social.

Goethe in a letter to a friend after the incident

Goethe and Napoleon

“Napoleon was the man! Always enlightened, always clear and decided, and endowed with sufficient energy to carry into effect whatever he considered advantageous and necessary. His life was the stride of a demi-god, from battle to battle, and from victory to victory. It might well be said of him, that he was found in a state of continual enlightenment. On this account, his destiny was more brilliant than any the world had seen before him, or perhaps will ever see after him.”

Goethe, Conversations of Goethe

Goethe, despite his disgust with the popular enthusiasm and naïve idealism of the French Revolution, was not just another constipated conservative lick-spittle of the nobility. The last period of his life saw his political analogue in Napoleon take flight, and Goethe was unabashed in his admiration of the man.

In that sense Goethe called him a Prometheus who had ignited a light for mankind, a light that made things visible that otherwise would have remained hidden. He had drawn everyone’s attention to himself.

Rudiger Safranski, Goethe: Life as a Work of Art

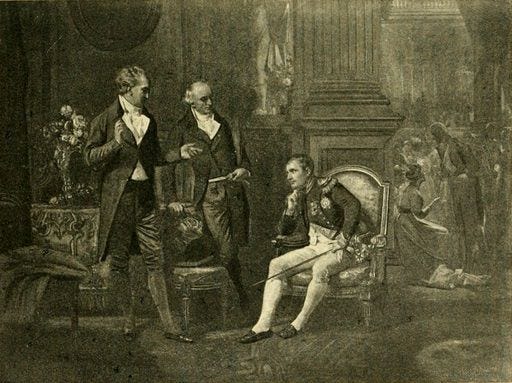

Goethe would meet Napoleon three times during his life. When they first met in 1808, Napoleon reportedly greeted the poet’s arrival with, “Behold, a man!”. They discussed Goethe’s translation of Voltaire’s Mahomet, with Napoleon criticizing Voltaire for putting a world-conqueror on the stage who gave such a poor depiction of himself. The conversation then moved to Werther, which Goethe later said Napoleon had studied quite thoroughly. He asked Goethe a very specific question about a literary device he had used at a particular point which the Emperor objected to. Goethe never revealed to his friends which part Napoleon had complained about, but he reportedly admitted to the younger French man that his criticism was correct. Finally they discussed theater, with Napoleon famously complaining about dramas of fate, and declaring “Politics is fate.” Their meeting would end with the Emperor politely inquiring about Goethe’s family and personal life, and later that year on October 15, 1808, awarding Goethe the order of the Legion d’honneur.

Goethe would have this to say about his dealings with the French Augustus:

I’m happy to admit that nothing higher and more gratifying could happen to me in my whole life than to stand before the French emperor in such a way. Without going into detail about our conversation, I can say that no superior has ever received me in that way, by allowing me with special confidence to be—if I may use the expression—myself, and clearly stating that my character was in accord with his (…) so that in these strange times, I at least have the personal assurance that wherever I may encounter him again, I will find him to be my friendly and gracious lord.

When Napoleon would finally be cornered in 1813, Goethe was in Teplitz staying with a German family, where they could hear the battle of Leipzig in the distance. The discussion began to dwell on the German uprising against Napoleon, and his possible defeat which the group was enthusiastic about, till Goethe finally broke his silence with a growl:

Rattle your chains as you will, the man is too great for you. You’ll never break them.

If only it had been the truth.

Goethe and Schopenhauer

“Dr. Schopenhauer sided with me as a sympathetic friend. We debated and agreed about many things, but in the end, a certain parting could not be avoided, as when two friends who have been walking together shake hands: One intends to go north, the other south, and then they very quickly lose sight of each other.”

Goethe, Annals

Our third Classical reincarnation, the Classical philosopher, would be the last to enter the stage of history and the last to depart. Schopenhauer met the German titan through his mother Johanna, who operated a famous salon and had won Goethe’s favor by opening her doors to Christiane Vulpius, Goethe’s lowborn mistress and eventual wife, while the rest of Weimar high society shunned her. They met in 1814, not long after Schopenhauer had published his doctoral thesis On The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, and Goethe had published his Theory of Color. Schopenhauer had sent his dissertation as a gift to the older poet, who had been greatly impressed by the intelligence it displayed.

Amid the tumult of the Napoleonic wars, Schopenhauer had returned home to Weimar to live with his mother. She had taken a lover 12 years her junior, a civil servant that Arthur frequently clashed with due to the man’s philistine, nationalistic character. The young Schopenhauer viewed his mother’s relationship as a complete disparagement of his father’s memory, and was constantly feuding with her. It was in this environment that the philosopher struck up a productive relationship with Goethe. The two would actively work together for a few months, till the young man could no longer bear his mother, and left Weimar.

While Goethe had been fuming over the lack of interest in his work on colors, he and Schopenhauer struck up a lively conversation in Johanna’s salon on the subject which transformed into a collaborative effort.

“Young Schopenhauer presented himself to me as a remarkable and interesting young man.”

Goethe, in a letter to Knebel

“Praise be his name in all eternity!”

Schopenhauer, in a letter after their first meeting

The two would collaborate on their theory of color, but it wouldn’t take long for Schopenhauer’s stubborn and bold personality to make an impression on Goethe, who wrote the following lines after a few weeks of their working together:

Teaching’s a chore, but could be a downright boon / If pupils didn’t turn teacher so soon

Schopenhauer agreed with the fundamental tenets of Goethe’s view, but saw himself as its completer who had actually worked it into a holistic theory. Goethe eventually became busy and tried to pawn off Schopenhauer on another one of their allies in the fight against Newtonian color, so that Schopenhauer responded with a blistering letter. It really speaks to his confidence that he was willing to write what he did to one of his idols and pseudo-father figure, essentially declaring that he had surpassed him. Goethe would reply coolly, remaining impressed by his young student despite his insubordination. The two men would be pulled in separate directions, though Goethe would forever remain to Schopenhauer an idol, from whom he quotes incessantly in all his works. Schopenhauer would continue sending his work to Goethe, and even claim that some of Goethe’s plithy sayings were informed by what he had shared with him. When Schopenhauer finally left, Goethe signed the following in the student album of the pessimistic and stubborn young man.

To rejoice in your own worth / You must grant worth to life on earth

Faust: The Work of a Lifetime

“Where shall I grasp you, never-ending nature?”

Goethe, Faust

Mephistopheles (to God) I’ve no remarks to make about the suns or planets, I merely see how mankind toils and moils. Earth's little gods still do not change a bit, are just as odd as their primal day. Their lives would be a little easier if You'd not let them glimpse the light of heaven— they call it Reason and employ it only to be more bestial than any beast.

Faust is Goethe’s masterpiece, and one of the greatest works of the entire Western canon. It is a book for which no description can do justice, and which ought to be universally read. It acts as the productive analogue to Goethe’s journey of self-realization: he had begun planning the work all the way back during his earliest youth as a child watching puppet shows, and was still fitting in the final pieces before his death. The book draws from his entire lifetime of experiences, and is divided into two parts which represent the Romantic and Classical inclinations within him, and which cumulatively form his vision of a new aesthetic sensibility which balances the two drives, real and ideal, subjective and objective, to form that harmonious whole which he had always sought. He poured in all the knowledge he had collected from his historical passions, scientific studies, civic duties, and intellectual relationships with the great experts of the era. It includes references to alchemy, geology, archeology, advances in currency, his work managing Weimar’s mines, and so much more, you truly feel the presence of a Renaissance man and genius while reading it.

If we return to the earlier Nietzsche quote concerning the ancient aesthetic sense which Goethe cultivated, all the features he specifically mentioned are to be found in Faust. Faust takes the entire scene of modernity and collapses it to the most simple and ideal forms, archetypes which capture the spiritual movement of an entire civilization. The story concerns the famous Faustian Bargain, wherein an old scholar, unsatisfied with the fruits of Reason, sells his soul to the devil, the spirit of nothingness himself, in exchange for monumental technical powers and world-mastery. This story is undoubtedly influenced by the philosophical world we have been discussing in previous posts, and with which Goethe was intimately familiar. Faust is, among many other things, Goethe’s response to the Sturm und Drang revolt against the enlightenment and to the pantheism controversy, his attempt to find a resolution to the dilemma of Reason and Nihilism through a return to the ideals of the ancient world and the Renaissance.

Faust tells the story of the symbolic Western hero of modernity, the all-knowing all-desiring all-despairing Faust. The text is written almost entirely in verse, and begins with a scene reminiscent of the book of Job, where God and the Devil dispute over whether reason has truly bettered humanity, and decide to make a bet over the soul of Dr. Faust, who has lived guided by reason to a greater extent than any other man. This dispute between God and the Devil is also a dispute between the ideal and the real: should man continue to strive for heaven, or should he renounce himself to worldly materialism. The Devil says he would be better off if he were fully weighed down to the earth and could accept material pleasures as the limit of his existence, while God affirms the divine part of him cannot be exiled.

Goethe’s devil, named Mephistopheles, is one of the most engaging and recognizable figures in Western literature. Goethe did not really believe in evil, his Spinozist inclinations tended towards a vision of the world wherein everything is redeemed in the whole, a vision which Nietzsche would inherit. His devil is consequently not some moralizing monster, but a playful, witty, and miserable agent of God. He represents the spirit of nihilism and proclaims himself a disciple of that ancient wisdom of Silenus: existence is something which ought not to exist. He is not some devious, cackling ur-power, but as much a sufferer as his victims, and his nihilistic realism contributes to the necessary growth of Faust. God does not have an antagonistic relationship with the devil, who is, like everything else, a necessary component of the whole, but welcomes him as a prod for human activity and growth.

FAUST The essence of such as you, good sir, can usually be inferred from names that, like Lord of Flies, Destroyer, Liar, reveal it all too plainly. But still I ask, who are you? MEPHISTOPHELES A part of that force which, always willing evil, always produces good. FAUST That is a riddle. What does it mean? MEPHISTOPHELES I am the Spirit of Eternal Negation, and rightly so, since all that gains existence is only fit to be destroyed; that's why it would be best if nothing ever got created. Accordingly, my essence is what you call sin, destruction, or—to speak plainly—Evil.

Faust himself is the quintessential Western man, who continues to represent our self-contradictions and character to this day. He is a learned master of the humanities and sciences who has by the time of the epic’s start seemingly exhausted the limits of human knowledge, and yet not pierced at all into the heart of existence. The mere “glimpse of heavenly light” which God has granted humanity is insufficient to comprehend his mysteries, and so Faust has slipped into a deep despair renouncing his achievements. He represents the insatiability of the West, its inability to settle into the kind of static, unaspiring cultural state that you find in the civilizations of the Orient.

From heaven he demands the brightest stars And from Earth's pleasures nothing but the best. And whether they come from near or very far, They cannot soothe his deeply troubled breast.Mephistopheles describes Faust

His despair drives him to the point of suicide, though in the end he lacks the will to do it, as he fears the possibility of nothingness. It is at this moment that Mephistopheles appears to him, promising to save him from his despair by showing him the full breadth of life’s pleasures. “Give up that silly metaphysics, and let’s go get you some teen pussy!” And so they make a bargain; Mephistopheles shall act as Faust’s servant and grant him his powers, and in exchange should Faust find satisfaction for a moment, his soul will then be forfeit and he will be Mephistopheles’ slave for eternity.

FAUST If ever I should tell the moment, I beg you, stay! You are so lovely! Then I am yours to lay in chains.

And so Faust and Mephistopheles embark on their adventures. Mephistopheles supplies material pleasures, Faust finds in them inklings of immaterial goods, so that the tension between the ideal and the real remains taut and drives their endless play. Man can neither have God or give him up, so he continues infinitely striving towards him.

The first part was complete in an early form, Ur-Faust, during Goethe’s Sturm und Drang days, and reflects the Romantic period of his career. It is thoroughly Gothic and Germanic, and tells the story of Faust’s bargain with Mephistopheles, whose power he uses to become a young handsome man and pursue a teenaged girl whom he has fallen in love with, named Gretchen after Goethe’s actual first love. He seduces her with the aid of his devilish companion, gets her pregnant, and upon his discovery murders her brother. Faust flees and for a moment forgets about her in the orgiastic excesses of Walpurgis night, and returns only to find she has drowned their child and been condemned to death. Faust attempts to use his powers to save her, but the young girl, sensing that he is corrupted, refuses and choose to face her fate. Mephistopheles and Faust flee the city, and hear a great cry from heaven: “She is saved!” Queue curtain fall on Part One.

Part Two begins with Faust refreshed and renewed by faeries, spirts of nature, cleansed of misery and guilt so that he can continue his necessary journey. In Part Two he no longer has the Gothic character of Dr. Faustus, but of a new Renaissance man who acts at differing times in the capacities of a courtly advisor, brave general, and ambitious lord. Mephistopheles is no longer as much of a Romantic devil either, but is now more like Faust’s worldly companion, a gentlemanly spirit of irony and cynicism. The second part is the Classical redemption of Faust, in which Goethe even stylistically imitated ancient Greek poetry in his German verse. The part is broken into five relatively separate acts which see Faust travel the world and engage in multiple practical spheres of life. He bewitches the Holy Roman Emperor with a plan to create value from nothing through paper money (and only creates inflation), leads an army against rebels, and travels through a mythical pastiche of the ancient world in search of Helen who has enchanted him. This journey from part one to part two, from an inward Romantic world of feeling to an outward Classical world of practical activity, mirrors the evolution of Goethe’s own life and the change from Werther to Wilhelm.