Knowing Nothing

The Philosophy of Fichte and Acosmism

“One has accused his philosophy of atheism quite unjustly, because Transcendental Philosophy cannot, as such, be atheist any more than can Geometry or Arithmetic. But for that same reason it cannot in any sense be theist either.”

“Truly, my dear Fichte,

I would not be vexed if you, or anyone else, were to call Chimerism the view I

oppose to the Idealism that I chide for Nihilism.”

Jacobi, Letter to Fichte

“For the Wissenschaftslehre, reason alone is eternal, whereas individuality must ceaselessly die off.”

Fichte, Foundation of the Entire Wissenschaftslehre

“The eagerness and subtlety, I should even say craftiness, with which the problem of "the real and the apparent world" is dealt with at present throughout Europe, furnishes food for thought and attention; and he who hears only a "Will to Truth" in the background, and nothing else, cannot certainly boast of the sharpest ears. In rare and isolated cases, it may really have happened that such a Will to Truth—a certain extravagant and adventurous pluck, a metaphysician's ambition of the forlorn hope—has participated therein: that which in the end always prefers a handful of "certainty" to a whole cartload of beautiful possibilities; there may even be puritanical fanatics of conscience, who prefer to put their last trust in a sure nothing, rather than in an uncertain something. But that is Nihilism, and the sign of a despairing, mortally wearied soul, notwithstanding the courageous bearing such a virtue may display.”

Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

I take my twitter handle, fugam vacui, from a public letter Jacobi directed to Fichte during the atheism controversy of 1799. It translates to “flight from the void”, and refers to Jacobi’s own attempt to escape what he saw as the necessary result of the philosophical speculation of the enlightenment: an all-consuming void within the european spirit.

The atheism controversy began when Fichte published an essay on God, reducing the divine to little more than an immanent moral order. A sterile God-as-moral-order hardly resembles the God to whom the pious pray, and accusations of atheism quickly followed. These accusations culminated in the public letter which Jacobi addressed to Fichte, and that ended the latter’s five year reign at the University of Jena. Fichte fled to Berlin to avoid the impending political persecution which he had opened himself up to from princely authorities, all too happy to be rid of a philosopher with a revolutionary streak. But despite this great effect, it must be noted that Jacobi’s letter never accused Fichte of atheism, and in fact defended him from this charge. What Jacobi instead argued in his letter was that Fichte, whom he declared the paradigm speculative philosopher, was guilty of nihilism.

The atheismusstreit was simply a continuation of the pantheismusstreit that Jacobi had begun a decade earlier. His position remained the same. All who made reason the supreme criterion of truth and denied any knowledge beyond its clutches were committed to a denial of individuality, human agency, and as result, life in its full sense. They reduced a living world of discrete beings and irrational truths to a mechanical chamber of phantoms. Jacobi’s initial target had been the rationalists of the aufklarung and Spinoza. But he began to expand the scope of his argument until he included practically all of his contemporaries. Kant’s copernican revolution had only inverted the tower of babylon rather than destroyed it. Fichte continued the Kantian path until he had developed a system just as nihilistic as Spinoza’s. Jacobi’s argument was that philosophy, and specifically the path of speculative reason, necessarily produced nihilism.

Nihilism is a difficult concept to pin down. It is intuitive in a way that can prove deceptive. Academics have often resorted to dividing it into various species (ethical, metaphysical, epistemological, etc), but this fails to properly appreciate what both Nietzsche and Jacobi have in mind when they charge modern Europe with Nihilism. Even worse, the word has suffered the terrible fate of popular usage, and like Fascism and so many other -isms is bandied about with little regard to its meaning. This word which possesses such a specific and important meaning for Jacobi and Nietzsche has degenerated to signify little more than the crime of objecting to whichever band-aid ideology a given pharisee wishes to promote as the solution to modern ills.

To return significance to this word we must return to its origin: the charge Jacobi laid upon Fichte and European philosophy. And so this post will first reveal the history and thought of Fichte himself, revealing how his imitation of Spinoza’s Hen Kai Pan (All in One) led to a philosophy of nothingness. A follow-up post will review Jacobi’s letter in detail and attempt to understand the first announcement of European nihilism. It will argue that Jacobi and Nietzsche use nihilism with the same essential meaning, and reveal the connection and difference between their philosophical projects.

I. The Rising Star

“Attend to yourself; turn your gaze from everything surrounding you and look within yourself: this is the first demand philosophy makes upon anyone who studies it.”

Fichte, First Introduction to the Wissenschaftslehre

“Jacobi’s famous argument against the thing-in-itself has to be understood in the light of his general critique of Kant. Jacobi regards the thing-in-itself as Kant’s final, desperate measure to prevent his philosophy from collapsing into nihilism. If this expedient fails—and it does of necessity, Jacobi argues—then Kant has to admit that he reduces all reality to the contents of our consciousness. It was the sad destiny of Fichte, Jacobi says, to develop Kant’s philosophy in just this direction. Fichte rid Kant’s philosophy of the thing-in-itself; but in doing so he revealed its true tendency and inner spirit: nihilism.”

Beiser, Fate of Reason

When Karl Leonhard Reinhold, who popularized Kant during the pantheism controversy, left his post as the first chair of Kantian philosophy at the University of Jena, the position passed to a thirty-three-year-old who had recently gained attention with a sensational essay. The Attempt at a Critique of all Revelation had been published at Kant’s behest, and connected transcendental idealism to the issue of divine revelation. The cogent argument and wit expressed in the tract impressed the general reading public so much they assumed it must have been written by Kant himself. The true author was Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a former Spinozist who had discovered Kant’s writings three years earlier in 1790 while working as an impoverished tutor.

Fichte was emblematic of the revolution occurring in European intellectual culture at the time. Born into humble origins, ever since the day a local baron observed his intellectual potential and sponsored his education he had committed himself to life as a freethinker. He had initially dreamed of a literary career, but upon arrival in the urban hub of Leipzig had to settle for odd jobs and tutoring to make ends meet. For a time, he drifted through various odd jobs and tutoring, just one more nouveau bourgeois among many, devouring the literary tracts and journals of the day. The young man quickly became a committed revolutionary and nationalist who would write in defense of the French Revolution and against the perceived tyranny of Europe’s aristocracy and monarchies who controlled public discourse and state policy.

Following his new semi-celebrity as the essay’s author, Fichte would immerse himself in the recent philosophical developments that were rapidly occurring. While he remained an admirer of Kant, he found himself increasingly swayed by the rising criticism of Kantian thought. He was greatly influenced by Reinhold’s attempt to correct Kantianism and agreed that was needed was an indubitable first principle, but was unconvinced by his ‘fact of consciousness’ as a real foundation for a complete idealist system. Reinhold’s principle—that all experience must involve both subject and object—failed to step outside experience and explain its existence and origin.

“Philosophy has to display the basis or foundation of all experience. Consequently, philosophy’s object must necessarily lie outside of all experience. This is a principle that is supposed to be true of all philosophy, and it really has applied to all philosophy produced right up to the era of the Kantians, with their “facts of consciousness” and hence of “inner experience.””

Fichte, Introduction to the Wissenschaftslehre

And so when Reinhold foolishly left his professorship of Kantian philosophy at Jena in 1974, it was Fichte who was selected to replace him, and who intended to use this opportunity to introduce his own philosophical system which had coalesced through his engagement with Kant, Spinoza, and their critics. His system would attempt to derive the conditions of experience from an unconditioned, indubitable, and purely subjective source: the absolute I.

Idealism vs Dogmatism

“We thus could express the task of philosophy in different words as follows: Philosophy has to display the basis or foundation of all experience.”

“We have no desire, however, to engage in a fruitless dispute over a word; and this is why we have long eased to lay any claim to the name “philosophy” and have given the name Wissenschaftslehre, or “Theory of Scientific Knowledge,” to the science that actually has to carry out the task indicated.”

Fichte, First Introduction to Wissenschaftslehre

Upon his arrival in Jena, Fichte immediately set to work presenting to his students a new critical system that expanded upon the foundation created by Kant and Reinhold. Fichte would continually develop this system for the rest of his life, and never produced a single canonical text of his vision the way Kant did with his Critiques. For our purposes, we will restrict ourselves to Fichte’s system as he described it during his tenure at Jena, which is when he had his greatest influence and was condemned by Jacobi.

Fichte introduces his thought by redefining two opposing philosophical methods originally described by Kant in the Critique of Pure Reason.

This critique is not opposed to the dogmatic procedure of reason (…) It is opposed only to dogmatism, that is, to the presumption that it is possible to make progress with pure knowledge, according to principles, from concepts alone (those that are philosophical), as reason has long been in the habit of doing; and that it is possible to do this without having first investigated in what way and by what right reason has come into possession of these concepts.

Kant, Preface to the B Edition

A dogmatist is someone who engages in speculative philosophy without any requisite critique of reason and its concepts, and consequently believes they can attain knowledge of things-in-themselves through concepts alone. Think of Spinoza believing he can reach the nature of the universe with just a set of axioms and the inferences which follow from them. In contrast, the critical philosopher (i.e… Kant!) considers the origins of our concepts and the extent of their applicability prior to engaging in metaphysics. Fichte refashions this dogmatist/critical idealist into a division much more concerned with ontology (what is) than epistemology (what can be known).

Fichte begins his inquiry by defining the task of philosophy as explaining the ground (read: cause, reason, explanation) of experience. He further claims that experience is always constituted by a subject and its object(s), and that any attempt to explain the origin of experience requires abstracting one of these two elements away. This leads to mutually exclusive species of philosophy. Dogmatism, which explains experience by abstracting away the subject so that things-in-themselves are the ground of experience. And Idealism, which explains experience by abstracting out things so that only the subject-in-itself remains. Perhaps this division will be more tangible and relevant if we contextualize it with an example.

For Fichte the dogmatist is someone who complete usurps autonomy from the I, and and attributes all true existence to the thing. He would categorize almost all of his contemporaries as dogmatists, but one must wonder how he would have reacted to the eliminative materialists of our day. The most widely accepted understanding of consciousness in our time is that it is an entirely epiphenomenal and secondary feature of existence. First there is matter, things, and at some point later the interactions of matter somehow conjure first-person subjects. For Fichte the most important fact about a philosopher is how they respond to this claim. He is entirely opposed to the way modern materialists as paradigm dogmatists understand being, and believes their position is entirely incapable of explaining the existence of first-personhood.

But this does not necessarily mean that Fichte can refute the dogmatists’ claims. Fichte considers dogmatism and idealism mutually exclusive and unassailable positions. There is no mediate argument through which one camp could refute the other, since they begin from entirely separate first principles. You either start from the position of freedom (autonomy of the I) or that of determinism (autonomy of the thing), and this a decision that is reached through personal experience and which reflects one’s character. Fichte here clearly follows in Jacobi’s footsteps, recognizing not only that philosophy requires a first principle, but that this first principle, as the ground of everything afterward, must be immediate (self-evident) and hence impossible to prove through mediate inferences. You cannot convince someone that they are free through syllogisms, they have to know it themselves.

Following Kant, Fichte considers freedom a ‘fact of reason’—something we can know with immediate certainty. For him, this recognition is the starting point of idealism. He further declares that “the thing-in-itself is a pure invention which possesses no reality whatsoever,” and in doing so clearly draws the battle lines. You can recognize your own freedom and become certain of it through self-reflection, and therefore follow the path of pure idealism, or you can project this freedom onto an abstract object independent of experience, and succumb to dogmatism. Idealism obviously has the upper hand, as Fichte believes it at least has some kind of access to its putative cause.

A little light-hearted excerpt before we proceed:

“When the dogmatist’s system is attacked he is in real danger of losing his own self. Yet he is not well prepared to defend himself against such attacks, for there is something within his own inner self which agrees with his assailant. This is why he defends himself with so much vehemence and bitterness. The idealist, in contrast, is quite unable to prevent himself from looking down upon the dogmatist with a certain amount of disrespect, since the dogmatist cannot say anything to him which he himself has not long since known and already rejected as erroneous. For one becomes an idealist only by passing through a disposition toward dogmatism—if not by passing through dogmatism itself. Confounded the dogmatist grows angry and, if it were only in his power to do so, would prosecute; while the idealist remains cool and is in danger of ridiculing the dogmatist.”

Fichte, Foundation of the Entire Wissenschaftslehre

Fichte and Self-consciousness

“(…) this philosophy is in complete accord with Kant’s and is nothing other than the Kantian philosophy properly understood.”

“‘Intellectual Intuition’ is the name I give to the act required of the philosopher: an act of intuiting himself while simultaneously performing the act by means of which the I originates for him. Intellectual intuition is the immediate consciousness that I act and of what I do when I act.”

Fichte, Second Introduction

Fichte’s project as he initially understood it was simply to rectify the perceived errors of Kantianism that critics had highlighted in the preceding years. He consequently presented himself as merely an exegete of the ‘true’ Kantianism, of idealism as Kant had intended it to be understood. And so when he sought a first principle, he returned to the Critique of Pure Reason.

In the Transcendental Deduction, Kant attempts to show that the categories are the necessary and universal conceptual conditions for all experience. One core element of this argument is apperception, or self-consciousness. Kant claims that self-consciousness is a condition of all representations.

“It must be the case that each of my representations is such that I can attribute it to my self, a subject which is the same for all of my self-attributions, which is distinct from its representations, and which can be conscious of its representations”

“It must be possible for the ‘I think’ to accompany all my representations; for otherwise something would be represented in me which could not be thought at all, and that is equivalent to saying that the representation would be impossible, or at least would be nothing to me.”

Kant, CPR

Self-knowledge occupies a unique position within Kant’s framework. He is adamant that we do not immediately intuit our self, and vaguely declares the “I think” a “simple representation”. But if you will recall from the post on Kant, he divides representations into two categories: concepts and intuitions. So what is the I?

Fichte begins his argument with the claim that the I is an intuition, and something of which we have immediate, certain knowledge. He further redefines the I not as a static entity which we observe, but an original activity present in all consciousness. The original act of consciousness, which is immediately present to itself via intellectual intuition, is the self-positing of the pure I. Fichte repurposes the term “posit”, which usually refers to the act of assuming a premise, and instead employs it to refer to the I’s act of self-discovery. Consciousness begins with pure self-consciousness.

To clearly convey that the I is not a thing, a static being, but rather this act of pure self-consciousness, Fichte coins a new philosophical term: the Tathandlung, or ‘Fact-deed’. The 'I' unifies the act of self-positing with the product of that positing: its existence lies in its acting.

“Accordingly, the question of whether philosophy should begin with a fact or with a tathandlung (i.e., with a pure activity that presupposes no object but, instead, produces its own object, and therefore with an acting that immediately becomes a deed) is by no means so inconsequential as it may seem to some people to be. If philosophy begins with a fact, then it places itself in the midst of a world of being and finitude, and it will be difficult indeed for it to discover any path leading from this world to an infinite and supersensible one. If, however, philosophy begins with a tathandlung, then it finds itself at the precise point where these two worlds are connected with each other and from which they can both be surveyed in a single glance.”

Fichte, Second Introduction

This is the foothold from which Fichte’s entire system springs. The starting point of philosophy lies in the affirmation of the absolute freedom and self-sufficiency of the pure I. This ‘I’ must be distinguished from the ‘I’ in ‘I am going to be busy tomorrow’. Fichte is not advocating solipsism as some of his contemporaries claimed. His claim is that experience, including the finite self, originates in an infinite and self-sufficient ur-self.

“The same talent possessed by any one rational being is also possessed by every other rational being. Indeeds, as we have often stated, and as we have repeated in the present treatise, the concepts with which the Wissenschaftslehre is concerned are concepts that are actually operative in every rational being, where they operate with the necessity of reason; for the very possibility of any consciousness whatsoever is based upon the efficacy of these same concepts. The pure I, of which our opponents profess to be unable to think, underlies all of their thinking and is present in their every act of thinking, for otherwise no act of thinking could occur at all.”

Fichte, Second Introduction

To distinguish his thought from prior systems and to highlight its intended goal of laying the foundation of all further knowledge, Fichte baptized his new system as the Wissenschaftslehre, or, ‘the science of knowing’.

The Wissenschaftslehre - Theoretical Reason

“The fundamental claim made by the philosopher as such is the following: Insofar as the I exists only for itself, a being outside of the I must also necessarily arise for the I at the same time. The former contains within itself the ground of the latter; the latter is conditioned by the former.”

“The essence of transcendental idealism as such, and, more specifically, the essence of transcendental idealism as presented in the Wissenschaftslehre, is that the concept of being is by no means considered to be a primary and original concept, but is treated purely as a derivative one, indeed, as a concept derived through its opposition to activity, and hence, as a merely negative concept. For the idealist, nothing is positive but freedom, and, for him, being is nothing but a negation of freedom.

Fichte, Second Introduction to the Wissenschaftslehre

Much like the challenge faced by eliminative materialists to explain how first-personhood could emerge from a world of objects, Fichte now faced the task of explaining how objectivity and necessity could arise from pure subjectivity and freedom. He would tackle this challenge in the first draft of The Foundation of the Entire Wissenschaftslehre. Having established his indubitable first principle in the self-positing of the pure I, Fichte set out to uncover the necessary conditions that sustain this foundational act, aiming to construct a complete a priori account of experience’s structure. When all the necessary conditions of experience had been elaborated and deduced from the I’s self-positing, the theoretical portion of the Wissenschaftslehre would be complete.

“If the presupposition idealism makes is correct, and if it has inferred correctly in the course of its derivations, then, as its final result (i.e., as the sum total of all of the conditions of that with which it began), it must arrive at the system of all necessary representations. It other words, its result must be equivalent to experience as a whole—”

Fichte, First Introduction to the Wissenschaftslehre

In Foundation of the Entire Wissenschaftslehre, Fichte traces the conceptual progression from the pure I’s self-positing to the individual self and experienced world. However, this is not a linear process of events (i.e., A happens, then B); rather, it is an analytical breakdown of what is, in reality, a unified, simultaneous act. Fichte connects this progressing series of metaphysical principles to the fundamental principles of logic. The result is confusing and obfuscates the relatively simple moves Fichte makes, and he would abandon this presentation in future versions. Nonetheless it would be quite influential as Hegel would imitate this union of metaphysics and logic in his own foundational text.

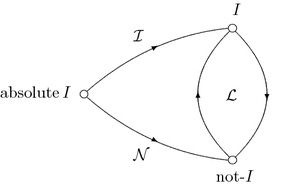

The Absolute/Pure I: Fichte begins with the self-positing of the absolute I, which he associates with the law of identity (A=A) and the concept of reality. This is our starting point of immediate certainty, and at this stage the I posits itself as unlimited and absolutely free, and is totally unconditioned. It is consequently also totally indeterminate and devoid of individuality.

The Not-I: Fichte argues that for this self-positing to be possible, it is necessary that the I simultaneously limits itself. To affirm its identity, the absolute I must also posit the not-I from which it distinguishes itself. This incredibly important move immediately introduces objectivity, and is identified by Fichte with the principle of non-identity (A != Not A) and the concept of negation.

The Finite I: Fichte then claims that as result of the limiting of the Absolute I, the finite I, the self, is necessarily posited against the Not-I. This limitation does not negate the absolute I entirely but divides it, establishing the finite self as distinct yet within the framework of the absolute, and Fichte identifies this action with the concept of divisibility, as well as with our old friend the principle of sufficient reason (A = in part Not A).

From the original self-positing of the absolute I, that most bare and primordial condition of cognition, has been elaborated a series of simultaneous acts through which the finite subject and finite object(s) are both posited within the Absolute I. Translated into plainer language, pure subjectivity discovers itself (i.e. attains the self-consciousness that is necessary for consciousness) only as limited by a phenomenal world. This world is not a set of mind-independant beings, but merely the negation of that original subjectivity. Fichte summarizes with the following:

“Hence the sum of that which is unconditioned and is purely and simply certain has now been exhausted, and I would like to express this in the following formula: the I posits in the I a divisible Not-I in opposition to the divisible I.”

Fichte, Foundation of the Entire Wissenschaftslehre

The Wissenschaftslehre - Practical Reason

“It is indeed possible what drove [Spinoza] to his system: namely, the necessary striving to produce the highest unity in human cognition. This unity is present in his system, the error of which consists only in the fact that he believed that he was inferring on the basis of theoretical, rational grounds, when he was in fact driven by a practical need, and that he believed he had established something actually given, when in fact he established merely an aspirational ideal, which could never be achieved. In the Wissenschaftslehre we will discover Spinoza’s highest unity, not as something that exists, but rather as something that ought to be but cannot be produced by us.”

Fichte, Foundation of the Entire Wissenschaftslehre

The unconditioned subjectivity that is the immanent cause of all experience, as a necessary condition of its activity, limits itself, and through this limitation produces finite subjects whose absolute freedom is subverted by a phenomenal world of necessity. So much for Fichte’s theoretical philosophy.

Fichte claims that by beginning with a ‘fact-deed,’ his philosophy unifies the theoretical and practical realms in a way Kant could not, bridging what is with what ought to be. By rooting both realms in freedom—both in the self-positing I of theory and the moral freedom of practice—Fichte sets up an integrated system that advances beyond Kant’s dualism. At a momentary glance, Fichte’s practical philosophy seems fairly uncontroversial and almost naively Kantian: the subject is immediately aware of his own freedom, is bound by the categorical imperative, and ought to live according to the dictates of reason and set the highest good as his end. But upon closer inspection, the ethical conclusions Fichte reaches are quite startling.

Fichte sees practical and theoretical reason as united in his philosophy because freedom, realized in the self-positing of the absolute I, serves as the originating principle for both what is and what ought to be. This unifying principle of freedom drives both the existence of consciousness and the moral imperative that binds conscious beings. Both his metaphysics and his ethics begin from the realization that we are free. But at the same time, we as finite individuals are also necessarily not free. From the abstract absolute freedom with which the Wissenschaftslehre began, we have reached the perspective of consciousness, caught between the I and Not-I. To be an I necessarily means to be finite and limited. And so the practical duty of the individual I is to aspire to that original unlimited freedom, even if it is never possible to achieve it.

“Yet, in accordance with the logical form of the judgment, which is that of a positive judgment, both concepts [viz., “human being” and “freedom”] are supposed to be united. They cannot, however, be united in any concept whatsoever, but only in the Idea of an I whose consciousness is determined by nothing whatsoever outside itself, but instead itself determines everything outside itself by means of its own sheer consciousness. But such an Idea is itself unthinkable, inasmuch as, for us, it harbors a contradiction. Nevertheless, it is established as our supreme practical goal. A human being should infinitely approach unattainable freedom.”

Fichte, Foundation

The I as idea serves as the practical counterpart to the theoretical principle of the absolute I. The human being in possession of reason, once he has discovered his own finitude, sets the idea of a fully autonomous and self-sufficient I, an I once more devoid of the Not-I, as its goal. The highest good in Fichtean ethics is the maximally rationally and autonomous state of an absolutely self-sufficient subject. But here we may begin to understand the charge which Jacobi laid upon Fichte. If it was through the Not-I that determinacy and division are introduced, then to set the absolute I as one’s end means to seek the annihilation of the individual. Fichte declares that we can never actually achieve this, but the fact that he declares it the highest aim of reason is shocking enough, even before he explicitly equates this I as idea with Spinoza’s God.

“In the Wissenschaftslehre we will discover Spinoza’s highest unity, not as something that exists, but rather as something that ought to be but cannot be produced by us.”

This seemingly insane idea does make a certain amount of sense given Fichte’s system. If reason is a universal faculty, identical in all rational beings, then the maximally free and hence rational world (Fichte follows Kant in identifying autonomy with rationality) would be one where individuals are entirely absorbed into this shared rationality. In such a world, individuality would be subordinate to reason’s universal form.

“Reason is the common possession of everyone and is entirely the same in every rational being.”

“The relationship between reason and individuality presented in the Wissenschaftslehre is just the reverse: Here, the only thing that exists in itself is reason, and individuality is something merely accidental. Reason is the end and personality is the means; the latter is merely a particular expression of reason, one that must increasingly absorbed into the universal form of the same. For the Wissenschaftslehre, reason alone is eternal, whereas individuality must ceaselessly die off.Fichte, Second Introduction

This was philosophy as Fichte presented it at Jena. The dissolution of all objectivity into the subject, and the denial of individuality as the fundamental precept of rational behavior. An infinite approach to the unlimited unity of nothingness, never reached but always sought. His time at Jena would be greatly influential, and the succeeding Idealists began where Fichte left off. But it would be in 1799 that the meteoric rise of the philosopher quickly met a precipitous fall.

II. The Falling Meteor

“Spinoza could not have been convinced of his own philosophy. He could only have thought of it; he could not have believed it.”

Fichte, Foundation

“Consequently, until such time as Kant himself explicitly declares, in so many words, that he derives sensation from an impression produced by the thing in itself, or, to employ his own terminology, that sensations have to be accounted for within philosophy by appealing to a transcendental object that exists in itself outside of us, I will continue to refuse to believe what these interpreters tell us about Kant.”

Fichte, Second Introduction

Fichte had a peculiar habit of so idealizing certain philosophers that he refused to believe they could be in real disagreement with him. Spinoza, Jacobi, and Kant were undoubtedly his greatest influences, and he constantly strove to convince himself and others that there was an inner harmony between the spirit of his system and the thought of his idols. Fichte had the advantage of Spinoza having been long dead, and hence unable to dispute their kinship. But his living idols would rebuke him, and thoroughly dissuade him from any future ideas that they shared a fundamental perspective. His fall from grace was defined by his relationships with these three philosophers; the latter two denounced him for his imitation of the first. One can only wonder what Fichte thought as he fled Jena—exiled from the world of prestige he had only recently been summoned to, shadowed by threats of legal punishment, and abandoned by his idols.

Fichte and Spinoza - The issue of Acosmism

“One further remark: if one oversteps the I am then one must necessarily arrive at Spinozism. In a very readable treatise, Concerning the Progress of Philosophy, Salomon Maimon has shown that Leibniz’s system, thought through in its entirety, is nothing other than Spinozism and that there are only two fully consistent systems: the Critical system, which recognizes this limit, and the system of Spinoza, which oversteps it.”

Fichte, Foundation

“[Spinoza] was convinced that a purely objective mode of reasoning must necessarily lead to his system, and he was right about this.”

Fichte, Second Introcution

Fichte had a very peculiar relationship with Spinoza. According to his Idealist/Dogmatist division of philosophy, Fichte as the paradigm Idealist should be as far as possible from Spinoza who is the paradigm Dogmatist. But this is not the case. It seems the idealist-dogmatist spectrum is more of a horseshoe than a line. To make either approach internally consistent, a shared premise must be adopted: monism. What binds Fichte to Spinoza despite his rejection of substance is his embrace of hen kai pan. Fichte’s conception of philosophy commits any consistent system to positing either an objective or a subjective original unity.

“Insofar as dogmatism can be consistent, Spinozism is its most consistent product.”

Fichte, Foundation

Fichte’s philosophy does not merely imitate Spinoza’s monism. When observe closely, his system appears as little more than Spinozism inverted. A infinite unity (I/God) is the ground of all experience and divides itself into subject (thought/finite I) and object (extension/Not I). The only difference is that we proceed from subject to object and set the One as both our metaphysical principle and our practical end. This intense similarity is an observation Fichte himself makes! He believes Spinoza is just a confused Idealist, and that he, Fichte, has not only perfected the Kantian system, but overcome Spinoza’s dogmatist error while retaining all the fundamental tenets of his system.

“Dogmatism’s supreme unity is in fact nothing other than the unity of consciousness, and it cannot be anything else; and its thing in itself is the substrate of divisibility as such, or the supreme substance, within which are posited both I and Not-I (Spinoza’s ‘intellect’ and ‘extension’).”

Fichte, Foundation

But in modeling his system on Spinoza’s, Fichte inherits its inevitable fault: acosmism.

Spinoza’s system ultimately commits him to a denial of the cosmos, of all individual beings and hence individuality itself. Spinoza famously defined determinacy (i.e. having properties through which you can be distinguished) as negation, declaring omnis determinatio es negatio (“all determination is negation”). By starting from an indivisible unity and defining all determination as negation, Spinoza makes it difficult to explain how individual entities—finite, determinate things—could emerge from the infinite. How does the unlimited ever become limited? In Spinoza’s case, this is the issue of transitioning from substance to modes. In Fichte, it is the issue of transitioning from the absolute I to the Not-I.

Fichte embraces Spinoza’s monism, his understanding of the infinite, and his definition of determinacy. Fichte begins with an infinite principle which is completely indeterminate, and only introduces determinacy with the Not-I, and explicitly connects this to the concept of negation. But he never gives an a priori reason why the absolute I would negate itself. He only introduces finitude a posteriori, by reasoning backwards from experience itself. It must have happened because it did happen. His ambition of producing an immortal foundation of all knowledge must flounder, for he is faced with either remaining at the standpoint of an infinite nothingness from which no thing can emerge, or of admitting finitude as a brute unexplainable fact.

We can appreciate the vehemence with which Kant and Jacobi in the same year denounced Fichte, when we see his philosophy for what it really is. Spinoza backwards, Spinoza turned idealist. The force of Kantian skepticism and its uber rational ethics united with the world-devouring Hen Kai Pan of Spinoza. Individuality emerges from the bosom of nothingness, and must return to its source. There is something vaguely Platonic in this return to the One, and I expect that is what Jacobi has in mind when he invokes the Platonic infinite in his letter. The motto of the Platonists was homoíōsis theō; “assimilate to God”. Fichte’s ethos could just as well be described as ‘assimilate to the void,’ reaching toward an absolute that is, paradoxically, without any independent, individual form.

I will conclude my excessive quoting from Fichte’s work with this final passage in which he summarizes his thought. It displays the vehemence with which that same acosmism, that dissolution of all individuality, which was merely a metaphysical accident in Spinoza, is by Fichte taken as an explicit goal.

“The I as an Idea is identical with a rational being. On the one hand, it is the latter insofar as the being has completely succeeded in exhibiting universal reason within itself, has actually become rational through and through, and is nothing but rational. As such, it has ceased to be an individual, which it was only because of the limitations of sensibility. On the other hand, the I as an Idea is the rational being insofar as this being has succeeded in completely realizing reason outside of itself in the world, which thus also remains posited within this Idea. The world remains in this Idea as a world as such, i.e., the substrate along with these particular mechanical and organic laws; but these laws are here geared completely toward exhibiting the final goal of reason. All that the Idea of the I has in common with the [absolute I] is this: in neither case is the I considered to be an individual. In the latter case, it is not thought of as an individual because I-hood has not yet been determined as individuality; in the former case, on the other hand, it is not thought of as an individual because individuality has vanished as a result of a process of cultivation in accordance with universal laws. (…) Philosophy in its entirety proceeds from [the absolute I], which is thus its basic concept. From this, it proceeds to the latter, to the I as an idea, which can be exhibited only within the practical portion of philosophy, where it is shown to be the ultimate aim of reason’s striving. (…) The latter is nothing but an Idea. It cannot be thought of in any determinate manner, and it will never become anything real; instead, it is only something to which we ought to draw infinitely near.”

Fichte, Second Introduction

Kant’s Letter

“My veneration for you is so great that you could not offend me in any way; certainly not by anything as easily explained as your delay in responding to me. But it would have depressed me, having achieved what I took to be your good opinion of me, to see it lost.”

Fichte to Kant, 1798

“There is an Italian proverb: May God protect us especially from our friends for we shall manage to watch out for our enemies ourselves. There are indeed friends who mean well by us but who are doltish in choosing the means for promoting our ends. But there are also treacherous friends, deceitful, bent on our destruction while speaking the language of good will, and one cannot be too cautious about such so-called friends and the snares they have set.”

Kant, Public Letter concerning Fichte 1799

Just as Fichte refused to accept that Spinoza was committed to determinism, he also rejected the notion that Kant genuinely believed in things-in-themselves. For Fichte, things-in-themselves represented a conceptual incoherence that he couldn’t reconcile with Kant's deeper insights. His denial of mind-independant objects was his greatest departure from Kant, and yet he maintained for years this was just the true Kantian revelation, and that others misread the Critique. He even begins the Wissenschaftslehre by declaring that any attempt to reconcile idealism with things-in-themselves (i.e… what Kant does!) was philosophically bankrupt and could only be attempted by fools. The paradox in Fichte’s critique is that, guided by Jacobi, he had indeed identified a genuine tension within Kantian thought. Yet his reverence for Kant prevented him from seeing it as an authentic fault in the system, instead reframing it as a misinterpretation in need of correction.

“The thought of a thing in itself is based upon sensation; but then, in turn, they want sensations to be based upon the thought of a thing-in-itself. Their earth rests upon the back of the great elephant; and the great elephant itself? — it stands upon their earth!”

Fichte, Second Introduction

When it became clear what Fichte truly believed, and he had succeeded in alarming all the princely authorities of Germany with both his impiety and his politics, all while declaring himself nothing less than the authentic Kantian disciple, the great philosopher of Konigsberg had no choice but to respond in one of his final publications prior to his death.

“In response to the solemn challenge made to me (…), I hereby declare that I regard Fichte’s Wissenschaftslehre as a totally indefensible system. For the pure theory of science is nothing more or less than mere logic, and the principles of logic cannot lead to any material knowledge, since logic, that is to say, pure logic, abstracts from the content of knowledge; the attempt to cull a real object out of logic is a vain effort and therefore something that no one has ever achieved. If the transcendental philosophy is correct, such a task requires a passing over into metaphysics. But I am so opposed to metaphysics, as defined according to Fichtean principles, that I have advised him, in a letter, to turn his fine literary gifts to the problem of applying the Critique of Pure Reason rather than squander them in cultivating fruitless sophistries. He, however, has replied politely by explaining that “he would not make light of scholasticism after all.” Thus the question whether I take the spirit of Fichtean philosophy to be a genuinely critical philosophy is already answered by Fichte himself, and it is unnecessary for me to express my opinion of its value or lack of value. For the issue here does not concern an object that is being appraised but concerns rather the appraising subject, and so it is enough that I renounce any connection with that philosophy.

I must remark here that the assumption that I have intended to publish only a propaedeutic to transcendental philosophy and the actual system of this philosophy is incomprehensible to me. Such an intention could never have occurred to me, since I took the completeness of pure philosophy within the Critique of Pure Reason to be the best indication of the truth of that work. Since the reviewer finally maintains that the Critique is not to be taken literally in what it says about sensibility and that anyone who wants to understand the Critique must first master the requisite standpoint (of Beck or of Fichte), because Kant’s precise words, like Aristotle’s, will destroy the spirit, I therefore declare again that the Critique is to be understood by considering exactly what it says and that it requires only the common standpoint that any mind sufficiently cultivated in such abstract investigations will bring to it.

There is an Italian proverb: May God protect us especially from our friends for we shall manage to watch out for our enemies ourselves. There are indeed friends who mean well by us but who are doltish in choosing the means for promoting our ends. But there are also treacherous friends, deceitful, bent on our destruction while speaking the language of good will, and one cannot be too cautious about such so-called friends and the snares they have set. Nevertheless the critical philosophy must remain confident of its irresistible propensity to satisfy the theoretical as well as the moral, practical purposes of reason, confident that no change of opinions, no touching up or reconstruction into some other form, is in store for it; the system of the Critique rests on a fully secured foundation, established forever; it will prove to be indispensable too for the noblest ends of mankind in all future ages.

The 7th of August, 1799.

Immanuel Kant

Kant’s public disavowal was a clear declaration that in his eyes the Critique had shut the door to speculative metaphysics forever, even if it bore an Idealist guise.

Jacobi’s Letter

“Yea, I am the atheist and the godless one, who, against the will that wills nothing, will tell lies, just as Desdemona did when she lay dying”

Jacobi, Letter to Fichte

The next post will review in detail the letter which Jacobi published and his analysis of Fichte’s thought, which culminated in the first philosophical usage of “nihilism”. We will use this original usage as the starting point for a definition and understanding of nihilism, and will relate Jacobi’s broader philosophical project to this crucial topic. I will then compare Jacobi’s understanding of nihilism to that of Nietzsche and argue that they use the term with the same essential meaning, and explain how Nietzsche’s response to nihilism differed from Jacobi’s.

Until next time!